1888–1920

Josef Albers was born in Bottrop, a coal-mining city in the industrial Ruhr Valley, on 19 March 1888. His father was a general contractor who was proficient in carpentry, house-painting, plumbing, and other crafts; for the rest of his life, Josef would consider that the way his father trained him in the materials and techniques of these crafts was of vital importance to him. Josef became a school teacher, initially instructing young children in all subjects, and then an art teacher. He painted, made drawings of the region, and became a printmaker; as a teacher, he had an exemption that kept him out of the army during World War I.

Annelise Else Frieda Fleischmann was born on 12 June 1899 in Berlin. While baptized and eventually confirmed in the Protestant church, she was Jewish: a fact that would prove highly significant later in her life. Her father was a successful furniture manufacturer, and her mother was a member of the Ullstein family when they owned the largest publishing company in the world, complete with its own airplanes to transport newspapers. Annelise’s mother arranged for her to learn figure drawing with a tutor and then to study art in the traditional Impressionist style popular in Germany. Growing up, Anni was fascinated with artistic process—whether the orchestra tuning up or her parents’ home being redecorated for costume parties—and the possibilities of artistic transformation.

1920–1933

Josef Albers arrived at the Weimar Bauhaus in 1920, the year after it was founded. He was supported by the Westphalian Regional Teaching System with the understanding that after a year he would return to the Bottrop region and resume his old job. But at the Bauhaus he became too intrigued with making assemblages out of discarded glass shards and bottle bottoms that he found in the town dump to consider leaving, and although he was told he had to try other media, he gained such respect from the Bauhaus masters that in 1925 he was one of the first students to be appointed a master. In 1922, Annelise Fleischmann had arrived from Berlin; she met Josef soon thereafter. She was initially turned down in her efforts to be admitted to the Bauhaus, but Josef helped her for a second set of tests, and she was admitted to the weaving workshop. They married in 1925. Anni would eventually direct the weaving workshop; Josef would work in carpentry, metalwork, glass, photography, and graphic design. At the Dessau Bauhaus, they lived in one of the Masters’ Houses, and in 1932, when the city government of Dessau stopped paying teachers’ salaries, they joined others at the Bauhaus when the school moved to makeshift headquarters in Berlin. In 1933, when the Bauhaus faculty, Josef among them, elected to close the school rather than comply with the Third Reich, the Alberses were left without jobs and with complete uncertainty about the future, especially because they already realized the significance of Anni being Jewish in the Nazi era.

1933

In July of 1933, Anni encountered the young American architect Philip Johnson in Berlin. They had already met at the Bauhaus, where Johnson admired Anni’s work. Anni invited Johnson up for tea to show him her latest work as well as the white linoleum floors in her and Josef’s flat. Johnson, baffled, said he thought that the textiles were by Lily Reich, who had shown them to him earlier and claimed them as hers; he wanted to right the injustice. He asked Anni if she and Josef wanted to go to America; without reflection, Anni replied, “Yes.”

Shortly thereafter, Josef was invited to teach at the newly-formed, pioneering Black Mountain College in North Carolina. The Alberses wired back saying that Josef spoke no English; they were told to come anyway. Everything concerning visas and the paperwork necessary for the trip went unexpectedly easily; in New York, there were “angels”—Anni’s term for them—in the background, Johnson and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller II and Edward M.M. Warburg helping push the permission through while paying for the Alberses’ first-class steamship fare.

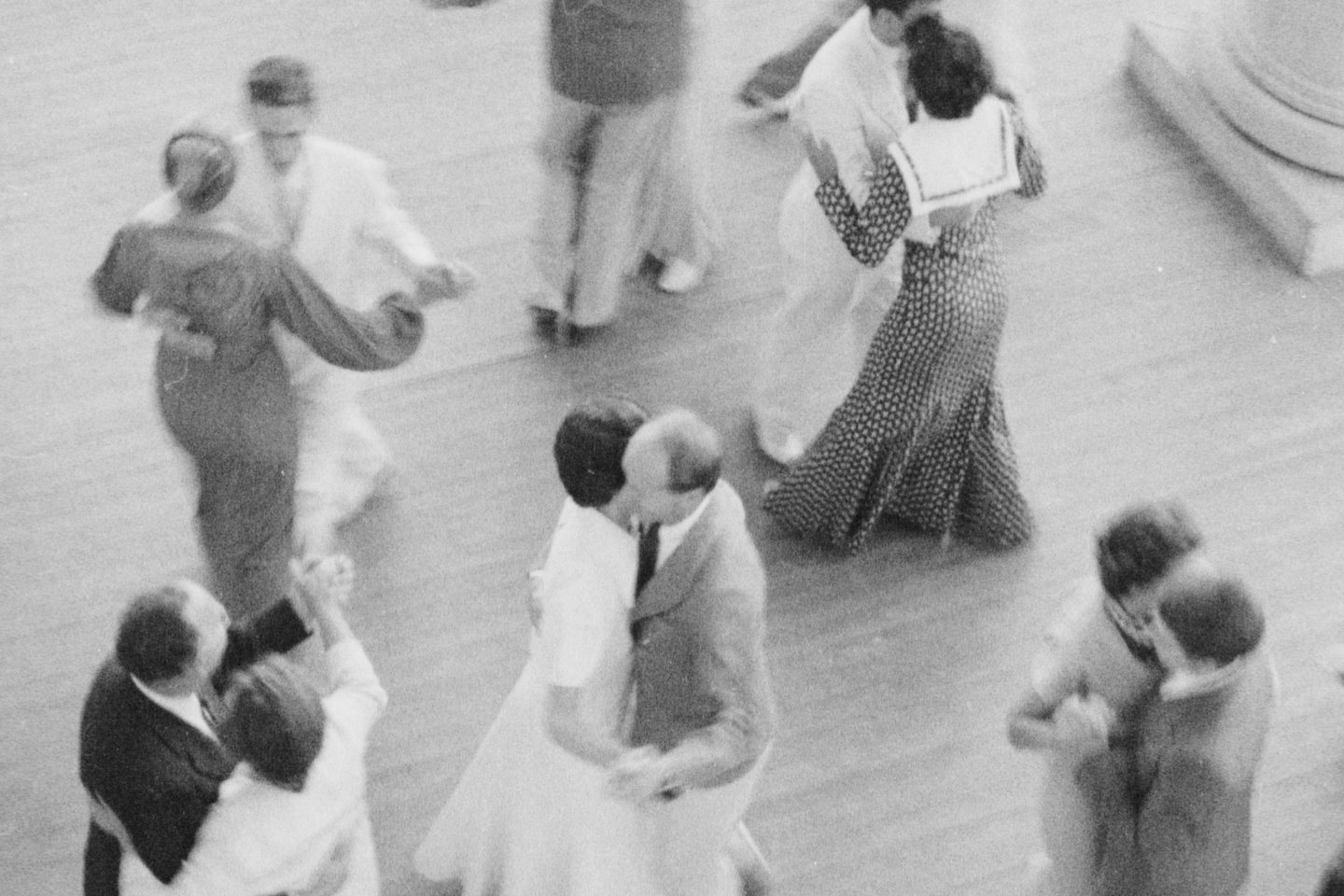

Josef and Anni Albers on their arrival in the United States, November 1933. Photo: Associated Press

1933–1949

From the moment that the Alberses arrive on the campus of the experimental Black Mountain College in rural North Carolina, they felt at home. They quickly made new friends, and Josef started teaching, initially with Anni translating for him, and then, shortly thereafter, on his own. His main language was visual, with the words of lesser importance, and students were wildly enthusiastic for the encouragement he gave them to experiment with form and color while gaining sureness of artistic techniques. Anni began to teach weaving and created wall coverings and drapery and upholstery materials while also making individual textiles to be regarded as independent artworks with no functional purpose. The Alberses traveled to Cuba in 1934, and in in 1936 went to Mexico with their friends Ted and Bobbie Dreier; it was the first of fourteen trips to the country where, they said, “art is everywhere.” By 1949, the internecine difficulties at Black Mountain caused the Alberses to leave and move to New York City, where, that same year, Anni was the first woman and the first textile artist to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

1950–1976

In 1950, Josef was appointed Head of the newly formed Department of Design at the Yale University, and the Alberses move to New Haven. After twenty-five years of marriage, it was the first time that they had lived in a house on their own, which meant, among other things, that Anni had to learn how to cook. Josef began to make his Homage to the Square paintings, while Anni continued as a textile artist, making materials for mass production at the same time that she created more of the works she called “pictorial weavings.” After Josef left Yale, they decided to remain in the region, where they had favorite restaurants and an overall support system. In 1963, Anni began to make prints; Josef had been doing so all along. They worked at various print workshops, Josef mainly doing Homages to the Square and the linear geometric prints he called Structural Constellations. Both Alberses were awarded various honorary degrees, and in 1971 Josef became the first living artist to have a solo retrospective exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In 1970, the Alberses moved to the suburb of Orange so as to be near the gravesites they had selected for themselves. On his eighty-eighth birthday—19 March 1976—Josef was admitted to the local hospital with heart problems; a week later, on a day when he was deemed healthy and ready to leave, he died.

1976–1994

Following Josef’s funeral, Anni oversaw the design of gravestones for both of them. They had selected their gravesites next to a roadway in the cemetery with the idea that whichever one of them survived could go by with the day’s post and read it while sitting in the car next to the grave of the other; Anni took up the habit as intended. Anni continued to design textiles and make prints, pursuing new techniques in both and inventing her own combinations of media. She also traveled a great deal, and in 1983 attended the opening of the Josef Albers Museum in Bottrop, for which she and the Josef Albers Foundation gave ninety-one paintings. Anni and the Foundation also made gifts of Josef’s artwork to museums worldwide. On 9 May 1994, Anni Albers died in their house in Orange.